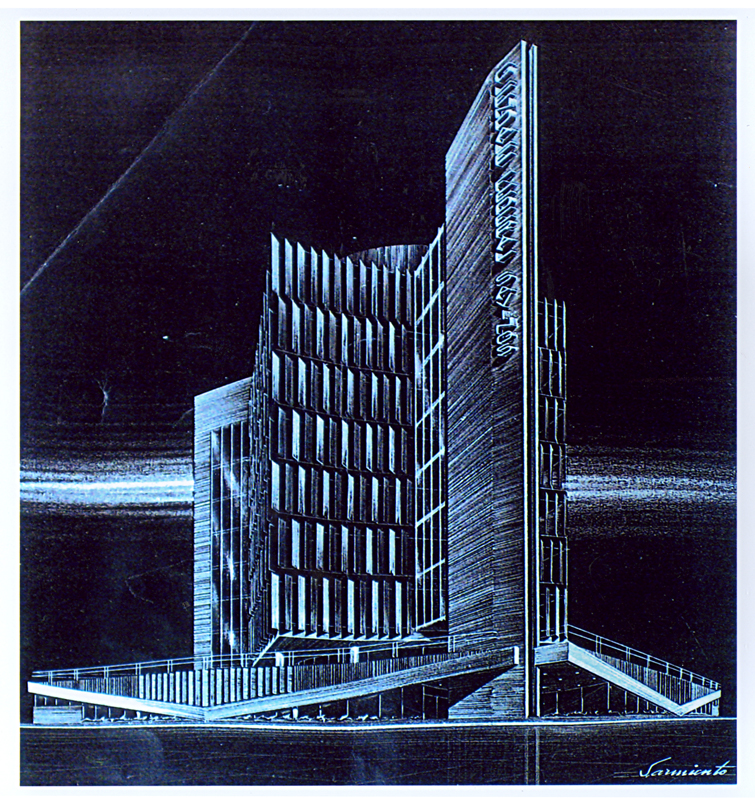

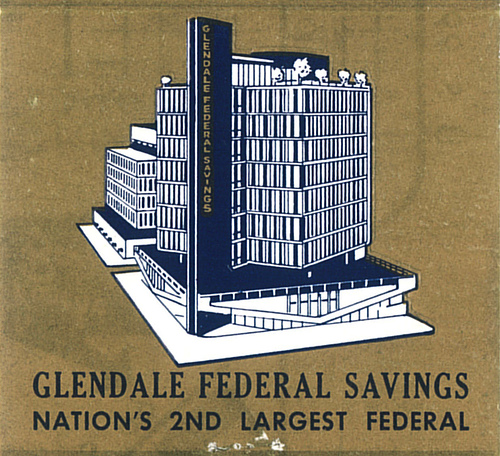

Glendale Federal Savings & Loan Glendale, CA 1959; 1962

Rendering by W.A. Sarmiento.

Exterior view c. 1960.

Summary

Glendale Federal Savings and Loan

401 N. Brand Blvd.

Glendale, California

Date of Construction: 1959; 1962

Architect: W.A. Sarmiento for Bank Building & Equipment Corp. of America; Maxwell Starkman (1962 addition)

Awards: Heritage Recognition Award, Pasadena and Foothill Chapter, California AIA, 2005

Designation: California Survey of Historic Landmarks

Interior c. 1960.

Detail view of vertical louvres, 2009.

Glendale Federal Savings and Loan has long been recognized as one of the best examples of the corporate International Style in Los Angeles.

In 1958, W.A. Sarmiento was commissioned by Glendale Federal Savings and Loan to design a new headquarters building that was modern and completely different from any other building around. Bank President J.E. “Joe” Hoeft gave his three basic requirements: It must be (1) modern and completely different from any other building around; (2) protected against the harsh Southern California sun; and (3) compliant with a new fire code requiring that stair towers be separated from the main building. Hoeft intended for this new ten-story structure to be a mark of his banks progressivism in Glendale, and knowing that Sarmiento had worked with renowned modernist Oscar Niemeyer and wanted to bring that spark of brilliance to his city.

Set at a 45 degree angle to the city grid, Hoeft gave Sarmiento the perfect site to create a bold architectural statement that for decades has been known as the “tower” of Glendale, featured on postcards, and described by Los Angeles architectural historian Robert Winter as “pure 1950s razzle dazzle.”

On the building’s fire brick red corner tower, a vertical sign proudly displayed its name for all to see as this was the city’s tallest building for many years. The corner tower functions as fire escape and elevator tower. The main cube structure is framed by concrete and glass with windows framed in aluminum, forming a grid of blue and white colors during the day, and glowing light with the louvers open at night. These distinctive blue louvers over the windows used solar power to pivot toward the angle of the sun throughout the day. Since the ground floors were independent of the tower allowing the incorporation of a skylight, sun still poured through the mezzanine level windows in order to provide visitors to the circular banking area on the ground floor with light. The exterior color scheme of deep red and seafoam green are primarily used, a commonly found color scheme on Sarmiento-designed buildings, as well as Vermont granite. The nearly 100,000 square foot interior featured a white terrazzo floor.

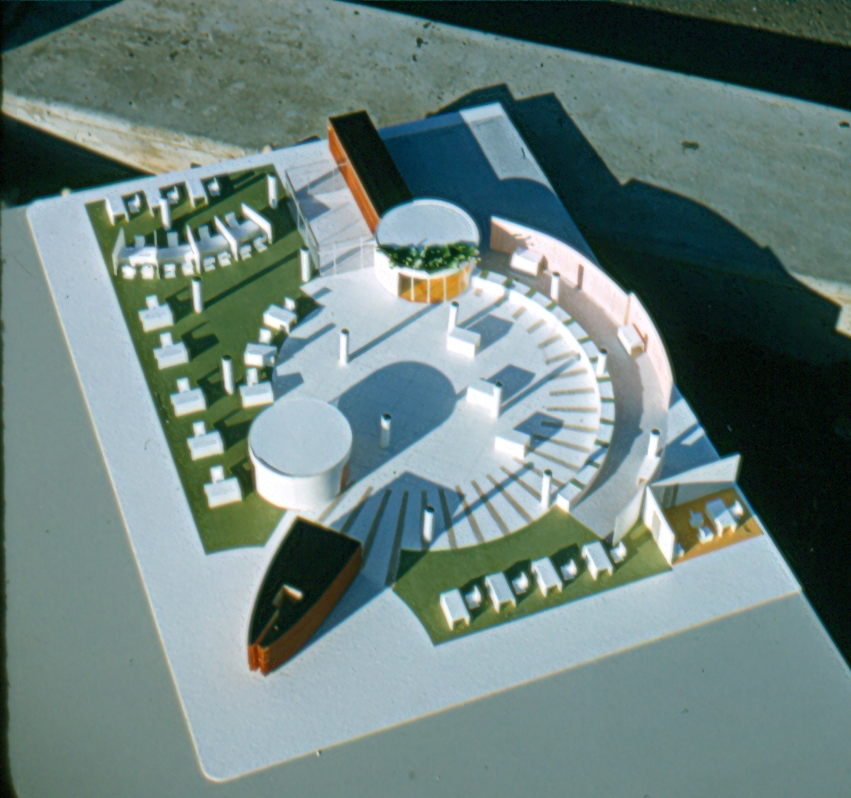

The new building was so successful that only four years later, in 1962, a new addition doubling the footage of the original was planned by architect Max Starkman. Starkman solved the problem of a site bisected by an alley by attaching his addition via a four-story skybridge. To tie his addition to the original building, Starkman similarly extended the floor plate of the upper floors beyond the window plane, and employed the same alternating light and dark solar operated louvers and anchored his addition with an enclosed stairwell featuring the same scored, red concrete. Starkman also created a broad patio to serve as a public plaza and attract people around the corner.

Glendale Federal Savings and Loan was bought out by Cal Fed in 1998 and the company moved its headquarters up the street. The building was subsequently sold to Nicholson Vertex Partners, who indicated their intent to remodel the building and to remove its character defining architectural features. In late 2000, the Glendale Historical Society, Los Angeles Conservancy, and concerned preservationists united to wage a preservation campaign that resulted in the building’s listing on the California survey of historic landmarks. With that listing, any permit to remodel required an environmental impact analysis.

Famed architectural photographer Julius Shulman lent his clout to the effort to save the building in 2004. In the effort to preserve the original building and its annex that he photographed in 1959, he described it as “an outstanding example of what an architect can achieve.” Shulman was encouraging the people of Glendale to nominate more buildings that contribute to Glendale in order to establish a better and more thoughtful process for rehabilitating significant modern structures. While preservationists nominated the building to the California Register of Historic Places and a state commission acknowledged the building’s significance, the owner stated objection to the listing and it was ultimately not listed.

At one point, the owners were close to signing an arrangement to have the property converted into a boutique hotel but the financing collapsed after September 11, 2001 and there was also discussion about converting the building into a housing complex. The building is now being leased as office space.

Largely retaining its architectural integrity, Glendale Federal Savings is the embodiment of distinguished mid-century modern architecture with enduring significance by retaining its central form and character. Viewed from any elevation, one can understand how Glendale Federal Savings became the symbol of the new downtown through its design, color, size, and dynamic presence, which is unlike any other architecture in the region.

Photo credits: Image of rendering courtesy of Special Collections Room, Glendale Public Library, Glendale, CA. Photos in carousel at bottom by Christine Madrid French.

To learn more about the significance of the history, architecture, and the rehabilitation, the following archival materials are provided.

Glendale Federal Savings Opening Day Guide (PDF)

“Architecture and Morality: W.A. Sarmiento’s Glendale Federal Savings Building” by Ara G. Corbett (PDF)

“A Different Brand of Americana: W.A. Sarmiento’s Glendale Legacy” by Ara Corbett (PDF)

Sign Installation Proposal, Historic Preservation Commission Staff Report, City of Glendale (PDF)

More photos: See more photos at emporis.com